September 1972 began with a memo from the Cabinet Secretary to British Prime Minister Edward Heath about the future of Northern Ireland, the Security Package and changes in the administration of justice (most notably the introduction of special courts). There’s quite a lot to digest within the memo, however, you can read it in full here.

The Future Policy group met again on the 19th of September. During this meeting, they covered 17 points of interest.

The Secretary of State thanked the members of the group for the time and effort which had been devoted to the preparation of the papers submitted to him. The group agreed that the papers would be submitted as prepared to the Prime Minister and if he so wished to other Members of the United Kingdom Cabinet.

The Secretary of State said that after the forthcoming Conference, he hoped to publish a Green Paper setting out the ideas which had been presented at the Conference thus giving Parliament and opinion in Northern Ireland an opportunity to consider them. It was then hoped that a White Paper and Bill setting out and providing for the proposed new arrangements for the government of Northern Ireland could be published before March 1973, when the initial operative period of the Temporary Provisions Act was due to expire.

The Secretary of State said that his mind was still open as to the precise form the new arrangements might take but that any solution to be successful would have to;

command, if at all possible, bi-partisan support at Westminster.

be regarded as fair by the rest of the United Kingdom and by international opinion generally

be acceptable to the broadest possible spectrum of opinion in Northern Ireland so that the people of the province would be prepared to cooperate in a real attempt to make it work.

A general discussion on the provision to be made for, and the timing of, a Referendum on the Border issue took place during which the following points were made;

That timing had to be related to the security situation, particularly now that it was becoming clear that pressure extending even to violence was possible from both extremes of opinion in Northern Ireland in an attempt to disrupt or affect the outcome of any Plebiscite.

While there were apparent advantages in holding a Plebiscite as soon as possible in an attempt to reduce the importance of the Border issue in the forthcoming Local Government Elections before moving on to detailed consideration of the future structure of government in Northern Ireland, there was also the associated danger that the holding of a Plebiscite, particularly a single-question Plebiscite, would raise rather than lower the temperature.

That the number and form of the question or questions to be included in a Plebiscite was of crucial importance.

That while a single-question Plebiscite could be mounted more quickly it might well over-simplify the issues involved and would be extremely difficult to answer without knowledge of the possible future structure of government in Northern Ireland. In this context, it was noted that the system of Plebiscites proposed in the paper on the "Irish Dimension" was designed to ensure that the final question relating to the unification of Ireland was not posed until the terms of entry would be known.

That a three-question Plebiscite would be a more appropriate vehicle for measuring middle-ground opinion and in particular for assessing what proportion of the minority would not wish to see a united Ireland at the point in time. In this context it was noted, however, that provision for a multi-question Plebiscite, particularly if associated with provision for future Plebiscites, would necessitate a complex COnstitutional Bill which would require a substantial amount of Parliamentary time at Westminster, which would not easily be made available.

That the precise wording of the question or questions would have to be carefully considered, particularly given recent experience in the field of the Social Sciences, where the wording of questions had been shown to affect answers. It was agreed that there would be an advantage when drafting the questions in having recourse to the expertise available to those concerned with the Government Social Surveys.

The Secretary of State said that the form and timing of the Plebiscite were difficult matters which would require further consideration and in this context, he invited the Future Policy Group to submit a further paper on the whole question of the Plebiscite.

It was noted that while in reality, the Government of the Republic appreciated that a united Ireland in the immediate future was neither practical nor desirable from their point of view they could not state this publicly. It was suggested, however, that the Republic's Government might, while retaining the nationalistic aspiration, be prepared to relinquish the territorial jurisdiction currently enshrined in their country's constitution. It was considered that even this would be a major step forward and a substantial contribution to any proposed settlement for Northern Ireland.

A general discussion of the application of Proportional Representation to elections for a Regional Assembly took place during which the following points were made;

While it was by no means certain that the introduction of Proportional Representation would make a substantial difference, at least in the initial stages, in the voting behaviour of the electorate or the composition of the Regional Assembly, at the very least it would do no harm and might do some good.

That there were difficulties associated with the introduction of Proportional Representation for a Regional Assembly while retaining the simple majority system for the Westminster Parliament.

That despite the difficulties it was accepted that the introduction of PR was a necessary prerequisite for the retention of a bi-partisan approach to Northern Ireland at Westminster.

That a beneficial by-product of the introduction of Proportional Representation would be the removal of Northern Ireland electoral boundaries from among the potentially contentious factors in local politics.

The Secretary of State said that he had become increasingly concerned about the small number of people in Northern Ireland who were prepared to become involved in and take responsibility for the problems of the Province. He, therefore, accepted the importance of giving careful consideration to the inclusion of non-political interests in any new devolved Assembly. He said that he would not, however, be attracted by the suggestion that non-political interests might be included in a unicameral Assembly but with limited voting rights. The Members of the Group agreed that the real choice was between the adoption of a bi-cameral approach or the co-option of the non-political interests to the Functional Committees of a unicameral Assembly.

Whatever the form of the Assembly in a devolutionary solution it was accepted that the salaries of the Members would require to be substantially higher than those paid to Members of the Stormont Parliament if people of real capacity were to be attracted to stand for election. The Secretary of State said that this problem had been faced at Westminster and would, he thought, be sympathetically considered by the Boyle Committee if a devolutionary solution were to be proposed.

The relative merits of Committee Government and the requirement that an appointed executive must receive the support of 75 per cent of the Members of the Assembly to take office were discussed. It was accepted that there were difficulties associated with both.

In the case of the Committee System, it was noted that there would be administrative difficulties in having a Committee responsible or a Department and that there would be presentational difficulties in getting a majority opinion inside Northern Ireland to accept a Committee structure, because of its similarity to Local Authority administration. It was also pointed out that even with a Committee structure some kind of weighted majority miGht be required in relation to the exercise of legislative functions by the Assembly.

It was pointed out on the other hand that the requirement of 75 per cent support for any administration could give too much power to minority groups in the Assembly who would wish to obstruct the whole system. It was suggested, however, that the functional nature of the work of the Assembly and in particular the introduction of a system of Functional Committees would facilitate cooperation between parties in the detailed work on services. It was also noted that there would be reserve powers which could be exercised if agreement could not be reached within the Assembly and that the existence of these powers would be a strong incentive for the Members of the Assembly to operate the system effectively.

It was agreed that for any devolutionary system to be a success there would have to be a consensus of opinion within the Assembly which was in favour of making the new system work.

The Secretary of State said that he agreed with the proposal that legislation providing for emergency situations should be on a United Kingdom basis as this would make the exercise of Special Powers more acceptable if such Powers continued to be, or again became, necessary.

It was agreed that the major difficulty in any devolutionary solution would be the allocation of responsibility for law and order and particularly the relationship between the Army and the Police in the context of a continuing substantial Army presence in Northern Ireland.

The Secretary of State accepted that if the future solution was to be on the lines of integration the Scottish Model presented a useful precedent on which to base consideration of detailed proposals. He pointed out, however, that from his own experience, the amount of travel involved for Ministers responsible for Northern Ireland in an integration solution constituted a very substantial strain and a real disadvantage.

The Secretary of State said that he welcomed the opportunity to discuss the papers submitted by the Group and that he would like to look again at some of the difficult areas which had been discussed after the Darlington Conference.

The Darlington Conference was held on the 25th of September on the issue of devolution with power-sharing. The Darlington meeting consisted of the Ulster Unionist Party, the Northern Ireland Labour Party, the Alliance Party of Northern Ireland, and Secretary of State for Northern Ireland William Whitelaw. The Social Democratic and Labour Party refused to attend because of the continuing operation of Internment. Some hard-line Unionists also refused to attend. There was no agreement on the shape of any future Northern Ireland government.

On the same day, Irish Taoiseach Jack Lynch met British Prime Minister Edward Heath.

As totally bizarre as it is to say given the continued violence and deaths in Northern Ireland, September was a much quieter month in comparison to the previous two or three. The main protagonists for trouble were the IRA, UVF, UDA and the British Army, all of whom had a hand in the further loss of lives.

Shootings

13/09/72 - The UDA opened fire inside the Catholic-owned Divis Castle Bar on Springfield Road, Belfast; one Catholic civilian, the owner's son (Patrick Doyle, 19), was killed.

15/09/72 - British soldier John Davis (22), was shot dead in an IRA sniper attack in the Bogside area of Derry.

16/09/72 - British soldiers manning a security post within the grounds of the Royal Victoria Hospital trade fire with three IRA units at night. One man was wounded.

16/09/72 - The British Army shot dead a UVF member (Sinclair Johnston, 27) during a riot in Larne.

17/09/72 - IRA volunteer Michael Quigley (19), was shot dead by the British Army during a riot in the Creggan area of Derry.

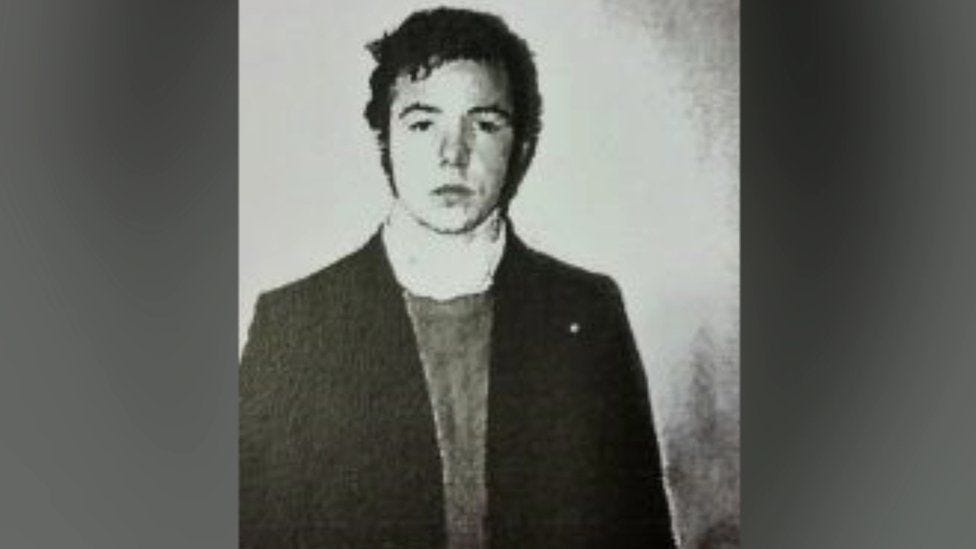

17/09/72 - Frank Bell (18), a Private in the British Army Parachute Regiment, was shot and seriously injured by the IRA while on foot patrol in Springhill Avenue, Ballymurphy, Belfast. Bell died of his wounds on the 20th of September 1972. Approximately a month later, Liam Holden was arrested for the killing by members of the Parachute Regiment. He was not handed over to the police but held in an Army base until he confessed to the killing. In 1973 Holden was convicted of the killing and sentenced to death by hanging. The sentence was later commuted to life imprisonment. Holden was released in 1989. In 2002, Holden brought his case to the Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC). He gave testimony of being subjected to a wide range of torture techniques to force his confession. On the 21st of June 2012, following a CCRC investigation, Holden's conviction was quashed by the Court of Appeal in Belfast. He died on 15 September 2022, aged 68.

18/09/72 - British soldier John Van Beck (26), was shot dead in an IRA gun attack while on foot patrol in the Lecky Road area of Derry.

20/09/72 - British soldier Francis Bell (18), was killed in a gun battle with the IRA on Springhill Avenue in Ballymurphy, Belfast.

20/09/72 - IRA Youth member Joseph McComiskey (18), was shot by the British Army during a gun battle, at Flax Street, Ardoyne, Belfast.

21/09/72 - A member of the UDR (Thomas Bullock, 53) and his wife (Emily Bullock, 50) were killed in an IRA attack near Derrylin, County Fermanagh.

22/09/72 - British soldier Stewart Gardiner (23), was killed in an IRA sniper attack in Crossmaglen, County Armagh.

26/09/72 - UDA volunteers shot dead a Catholic civilian (Paul McCartan, 52) near his home on Park Avenue, Strandtown, Belfast.

27/09/72 - British soldier George Lockhart (24), was killed in an IRA gun attack in Derry.

27/09/72 - Civilian Alexander Greer (54), was killed in an IRA gun attack at the corner of Ligoniel Road and Mill Avenue, Belfast.

27/09/72 - Daniel Rooney (19), a Catholic civilian, was shot dead by a member of an undercover British Army unit at St James Crescent, Falls, Belfast. An 18-year-old man was also shot and injured in this incident.

27/09/72 - Civilian James Boyle (17), was found shot by Flush River, Elswick Street, off Springfield Road, Belfast. It was believed that the UDA were responsible.

28/09/72 - The UVF shot dead a Protestant civilian, Edward Pavis (32), at his home on Glenvarlock Street, Belfast.

29/09/72 - The UVF shot dead a Protestant milkman, Thomas Paisley (49) while carrying out a robbery at a farmhouse on Straid Road, Ballynure, County Antrim.

29/09/72 - An IRA volunteer (James Quigley, 18) and a British soldier (Ian Burt, 18) were killed in a gun battle in the Lower Falls area of Belfast.

30/09/72 - British soldier Thomas Rudman (20), was shot dead by an IRA sniper in the Ardoyne area of Belfast.

30/09/72 - A Catholic civilian (Francis Lane, 23), was found shot dead on waste ground at Glencairn Road, Glencairn, Belfast. It is believed the UDA was responsible.

Bombings

02/09/72 - The headquarters of the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP), in Glengall Street, Belfast, was severely damaged by a bomb.

06/09/72 - UDA volunteers threw a bomb into the home of Republican Labour Party councillor James O'Kane on Cedar Avenue, off Antrim Road, Belfast. A Catholic civilian (Bridget Breen, 33) was killed, and five others (including three children) were wounded.

10/09/72 - British soldiers Douglas Richmond (21), Duncan McPhee (21) and William McIntyre (23), were killed in an IRA landmine attack on a British Army armoured personnel carrier near Dungannon, County Tyrone.

14/09/72 - The UVF exploded a car bomb outside the Imperial Hotel on Cliftonville Road, Belfast, which killed three civilians, two Protestants (Andrew McKibben, 28, and Martha Smilie, 91), and a Catholic (Anne Murray, 53, who died of her wounds two days later, on 16 September 1972). You can watch a news report on the incident below.

18/09/72 - Civilian Edmond Woosley (23), was killed by a booby trap bomb attached to a friend's stolen car, which exploded when he attempted to open the door, Glassdrumman, near Crossmaglen, County Armagh.

30/09/72 - The UVF exploded a car bomb at Conlon's Bar, Belfast, which killed two Catholic civilians, Patrick McKee (25) and James Gillen (21).

Some recommended reading based on research for this instalment of Tales of The Troubles.