January 1980: "Irish heroes on the blanket in Long Kesh"

In January 1980, Pink Floyd's double album "The Wall" hit number 1. One of the most famous tracks on the album was “Another Brick In The Wall”. Weirdly, in Northern Ireland, every time a new prisoner joined the hunger strikes, this was another brick in the wall for the IRA propaganda machine…

Political Developments in January 1980

January began with John Hermon succeeding Kenneth Newman as Chief Constable of the RUC.

On the 5th, Edward Daly, Bishop of Derry, sent a letter to Secretary of State for Northern Ireland Humphrey Adkins regarding the ongoing hunger strikes.

Dear Mr. Atkins,

I have been very concerned about the situation in the H Blocks in the Maze Prison for some considerable time. I visited there about eighteen months ago and was horrified by what I saw. I wrote to Mr Mason about this and discussed the matter with him on several occasions.

Whilst I accept that the form of protest is objectionable and that it is undertaken by the prisoners on their own initiative, I still feel that something should be done to try and break the deadlock. It is terrifying to think that some of these men have chosen to live in these conditions for such a long period of time. I think that they must be saved from themselves. I dread to think of what the mood of these men is likely to be when they are eventually released.

I feel very strongly that, without any surrender of principle, some strategy could be devised whereby all prisoners in N. Ireland could be permitted to wear their own clothing. I do feel that the present type of prison uniform is excessively humiliating and Dickensian. I don’t think that such a decision would, in any way, weaken prison security. I do think it could go some way towards easing the present tense and worrying situation.

The H Block situation is the main propaganda plank that the IRA has here and abroad. I think it would be unwise to assume that there is a total lack of concern or interest amongst the minority population here about this problem. Although there have been relatively small attendances at recent H Block protests and marches, I know, from my own contacts with many of my people, that there is significant concern in the Catholic community about the H Block problem. There is considerable sympathy, especially for the families of those held there. Many of these families are good and decent people who are respected in their own localities. I hasten to add that the Catholic community is completely revolted by the callous murders of prison officers. My own experience would also suggest that support for the IRA is at its lowest ebb ever in the Catholic community. I am hoping that this attitude will persist. That is why I am worried about the Maze situation. The death of a prisoner there would certainly signal a massive IRA propaganda campaign that might attract some more support to them, especially amongst the young.

I would ask you to give serious consideration to this matter. I believe it to be most important and urgent.

The talks called by Secretary of State for Northern Ireland Humphrey Atkins got underway at Stormont on the 7th. As part of the wider Atkins talks, a constitutional conference was arranged at Stormont involving the DUP, the SDLP, and the Alliance Party. The UUP refused to take part in the conference. Atkins conceded a parallel conference which would allow the SDLP to raise issues, in particular an 'Irish dimension', which were not covered by the original terms of reference. The DUP refused to get involved with the parallel conference. The Atkins talks continued until the 24th of March 1980 but did not succeed in achieving consensus amongst the parties.

On the 16th, Private Secretary to Humphrey Adkins, Mr A Brown, sent a letter to A Jackson regarding a telephony call from former SDLP leader Gerry Fitt.

Mr Jackson

CONVICTED IRA PRISONERS

Mr Gerry Fitt telephoned me this afternoon to seek our help in providing him with some information. He told me that, since his resignation as leader of the SDLP, he had received a number of unpleasant letters, mainly from the United States, generally abusing him but, in particular, making the point that he was not supporting the "Irish heroes on the blanket in Long Kesh".

Mr Fitt is keen to respond to this correspondence and would like to include in the letters he is going to send, two or three paragraphs which comment on the "Irish heroes on the blanket who are British prisoners of war in Long Kesh". He has something like the following in mind:

"There are X convicted IRA men in the Maze Prison. They have been convicted through the normal judicial processes for some of the most serious offences against the criminal law. They are not political prisoners imprisoned for their beliefs. Of the total of X, Y are taking part in the dirty protest. Perhaps some sentences to deal with the fact this is self-imposed. Of these, Y men (a) have been convicted of murder, (b) have attempted murder (c) of causing an explosion. Amongst these so-called heroes are men who have murdered and maimed innocent men, women and children, for example, …………… (give some examples).

I do not see why we should not help Mr Fitt in this, and I would be grateful if you would let me have some suitable paragraphs. Mr Fitt said that we need not worry about his respecting the confidentiality of our providing him with his information as he would have more to lose than we would if it came out that he was using information provided by the Northern Ireland Office. He said his critics would seize upon this as further evidence as he was "a tool of the British".

Member of Parliament for North Down James Kilfedder launched a new political party called the Ulster Progressive Unionist Party (UPUP) on the 17th. The UPUP later changed its name to the Ulster Popular Unionist Party; UPUP.

On the 29th, Humphrey Adkins replied to Gerry Fitt;

Dear Gerry,

You telephoned my office last week and asked if we could provide you with some material which you might be able to use in your reply to letters sent to you, mainly from the United States, about the protest campaign in three of the cell blocks at Maze Prison.

I have attached four paragraphs, which I hope you will find helpful in replying to this kind of correspondence. I should be glad, at any time, to let you have some more detailed background if you would find this of any value.

You refer in your letter to Irish heroes on the blanket in Long Kesh". I find this a curious description, not in any way justified by the facts. What we have are some 350 prisoners who have been convicted through the criminal courts of some of the most serious offences; who, before being sentenced, had available all the normal safeguards, including the laws of evidence, access to legal representation and right of appeal - without leave - to a higher court; and, who themse1ves have created conditions of squalor in order to draw attention to their claim to be treated differently from other sentenced prisoners.

Much is said and written about "political prisoners". Nobody feels more strongly than I do about the right to freedom of political expression, but the men taking part in this protest are not imprisoned for their beliefs. Of the prisoners taking part in the protest at the end of last year, 55 had been convicted of murder, 38 of attempted murder', 84 of firearms offences and 100 of explosives offences. These figures are bad enough, but they do not adequately depict the desperate trail of grief and anguish which many of these crimes have left behind. One more murder or maiming is just one more on the total, but to the family concerned it is the sad and irretrievable loss of, or injury to, a loved one.

Among these so-called "heroes" - it is nothing less than an affront to use this word - are men who, for example;

(i) bombed a shop in which a young woman was burned to death.

(ii) murdered a soldier and a civilian searcher under cover of a University "Rag Day" parade; and

(iii) placed bombs on a suburban train in which a woman of 22 was killed and several other innocent passengers injured.

(iv) shot a man on an errand of mercy taking hardboard to repair houses in the Lower Falls area of Belfast which had been damaged by a bomb blast.

I can not accept for one moment that these men, who make up less than one-third of the total number of sentenced prisoners accommodated in the cell blocks at Maze Prison, have any claim whatsoever to be treated differently from other persons sentenced to imprisonment through the courts. I would like to think that despite the arguments of those who support the protest campaign - which itself is causing so much anxiety among prisoners' relatives and friends - you will reflect on what I have said before you continue to give your own support to this misnamed "cause".

Adkins also replied to Edward Daly’s letter on the 31st;

Dear Bishop,

Thank you for your letter of 5 January about the protest campaign at Maze Prison against the refusal of special category status.

I was heartened to note your belief that support for the IRA is at its lowest-ever ebb in the Catholic community. Certainly, the Government wishes to do nothing which might rekindle support for the paramilitary organisations, and we are well aware that the IRA's main propaganda effort is being centred on the difficult and unpleasant situation in the three cell blocks in which the protest is being carried out. They have made no secret of their view that to win the war, as they put it, they must first win on the question of "status".

It goes without saying that we should like to see an end to the protest. We have in Northern Ireland a humane prison regime which provides first-class facilities for work, training and education, and arrangements for visits and recreation, which are in advance of those in Great Britain. I am sure you will have noted that the independent inquiry into the United Kingdom Prison Service under the Chairmanship of Mr Justice May described the prison accommodation in Northern Ireland as the best in the United Kingdom. It is in those conditions that this uniquely offensive form of protest is taking place.

You suggest that something should be done to break the deadlock, perhaps by allowing all prisoners in Northern Ireland to wear their own clothes. I do not think that the prison uniform, which is accepted by the great majority of sentenced prisoners, can, on any reasonable view, be regarded as humiliating or degrading. It is not always realised that prisoners in Northern Ireland who conform with Prison Rules are allowed to wear their own clothes during association periods, so in effect, uniform is only required to be worn during the working part of the day. Prison uniform is a feature of prison regimes throughout the United Kingdom, and if a change were to be made in the present arrangements for male prisoners it would have to be on a UK basis and for considered policy reasons; not as a concession in response to a terrorist campaign of murder, bombing and other violence.

We are constantly reviewing the arrangements for handling the protest, and I would like to remind you of the steps which we have already taken to contain the consequences of the prisoners' actions. The cells are being cleaned every few days; each dirty cell is repainted after every fourth cleaning; we have reviewed and improved the medical regime and taken various public health measures; we have replaced the window coverings each time the prisoners have broken them, and we have put books and newspapers in each wing of the blocks concerned, which the prisoners could easily use if they chose to do so.

The attitude of the prisoners to attempts by the authorities to improve their self-imposed conditions is illustrated by the events of 30 November. On that morning, the Prison Governor issued chairs to the protesters, one to each prisoner. Late in the evening, the prisoners acted in concert to destroy nearly all the chairs. Then they used the pieces as weapons to destroy first the inner metal window grilles and then the outer translucent perspex shields. Subsequently, attempts were made to claim that prisoners had been beaten up whilst the wreckage was being removed, when in fact, only one injury of any significance occurred and that through a prisoner standing on a piece of the broken perspex.

I recognise that your proposal that prisoners should no longer be required to wear uniform is made with the sincerest of motives; the same suggestion has already been put to us by a number of other people. But I am afraid that suggestions of this kind do not go to the heart of the matter; the dirty protest is not really about the wearing of uniform or prison work. The aim of the protesting prisoners and those who support them from outside is to force the Government into granting concessions which, in stages or all at once, would amount to the re-establishment of special category status. Once this had been attained, the next drive would no doubt be for an amnesty or promise of amnesty. Such a chain of events would allow the terrorist organisations not only to control those of their members who were imprisoned but also to offer a kind of indemnity for the commission of further violent crimes. The lives of many more young people would then be perverted through their being caught up in the webs of the terrorist organisations.

I do understand the community pressures which the Maze protest has generated. It must be very difficult for the families and friends of the protesting prisoners to sift fact from fiction when they are consistently confronted by lurid and false allegations from the propagandists. I must be frank, however, and say that I see no easy solution to all the community aspects of the problem. The responsibility of the Government and the prison authorities is to maintain the rules of the prison, sustain hygiene and care for the prisoners as humanely as possible, and I am satisfied that this is being done by the Governor and his staff faithfully and unremittingly despite the unique provocations and successive murders of prison officers.

It must be for the prisoners themselves and those who direct and influence them, to decide when to put an end to this bizarre attempt to blackmail the Government. You are well aware of the nature of the kinds of crimes which many of the prisoners have committed and the trail of grief and suffering left behind. The Government is not prepared to abdicate its responsibility by giving special treatment or concessions to such persons serving their sentences in prison.

I am, of course, most ready to discuss all these matters with you, if you wish.

Yours sincerely, Humphrey Adkins.

Shootings, Beatings & Other Deaths in January 1980

January 1st.

Undercover members of the British Army, Gerald Hardy (18) and Simon Bates (23) were shot dead by other undercover members of the British Army while they were setting up an ambush near Forkhill, County Armagh.

Doreen McGuinness (16), a Catholic teenager, was shot dead by British soldiers while she was 'joy-riding' in a stolen car on the Whiterock Road, Ballymurphy, Belfast.

January 2nd.

An ex-UDR soldier, Samuel Lundy (62), was shot dead by the Provisional IRA, at his workplace, Kingsmills, near Bessbrook, County Armagh.

January 3rd.

RUC officer Robert Crilly (60) was shot dead at his workplace, Main Street, Newtownbutler, County Fermanagh, by the IRA.

January 4th.

Alexander Reid (20), a Catholic civilian, was found beaten to death in a derelict garage in Berlin Street, Shankill, Belfast. It’s believed the UDA were responsible.

January 12th.

RUC officer David Purse (44) was shot dead when an IRA unit ambushed a foot patrol at the main gate of Seaview football ground, Shore Road, Skegoneill, Belfast.

January 13th.

Civilian John Brown (47) died seven months after being shot by INLA members during an armed robbery at the post office where he worked on Main Street, Blackwatertown, County Armagh.

January 18th.

Prison officer Graham Cox (35) was shot dead by the IRA while driving home from Magilligan Prison, Limavady Road, Stradreagh, near Derry.

January 21st.

Anne Maguire was found dead in what was believed to be a case of suicide. Anne Maguire was the mother of the three children who were killed in an incident on the 10th of August 1976 which led to the formation of the Peace People.

January 26th.

British soldier Errol Pryce 21) was shot dead while on foot patrol by an IRA sniper on Whiterock Road, Ballymurphy, Belfast.

If you’d like to support the newsletter, why not buy me a ☕️ ?

Bombings in January 1980

January 6th.

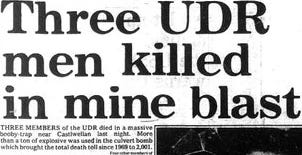

Three members of the UDR, Robert Smyth (18), James Cochrane (21) and Richard Wilson (21), were killed by the IRA in a land mine attack near Castlewellan, County Down. These deaths brought the 'official' death toll, as compiled by the RUC, to over 2,000. RUC figures do not count those killed outside of Northern Ireland.

January 17th.

Three people were killed and two injured when a bomb, being planted by the IRA, exploded prematurely on a train at Dunmurry, near Belfast. One of those who died was a member of the IRA (Kevin Delaney (26)), and the other two people (Obayoni Olorunda (35) and Mark Cochrane (17)) were civilians.

Thanks very much for reading. I hope you found it interesting and will come back on Thursday!

I appreciate everyone who recently clicked the heart icon ❤️ at the bottom. It makes it easier for others to find this newsletter.

Thanks for the support!

I’ve also recently released Tales of The Troubles: Volume 1. The Early Years - 1960s. Check it out. It would be a great addition to your library or a gift for someone for Christmas. Stay tuned for Volume 2, covering the 1970s.

If you’d like to let me know what you think of today’s instalment, please comment below.

Some recommended reading based on research for this instalment.

Lost Lives: The Stories of the Men, Women and Children Who Died as a Result of the Northern Ireland Troubles by David McKittrick, Chris Thornton, Seamus Kelters and Brian Feeney.