On the 4th of January 1969, you may have been kicking back listening to Marvin Gaye’s smash hit ‘I heard it through the grapevine’, as it hit the top of the US charts. However, across the pond in Northern Ireland, more trouble was escalating in Derry/Londonderry.

The People's Democracy (a civil rights group that had come into existence only a few months earlier) organised a march from Belfast to Derry which came under attack by Ulster loyalists whilst passing through Burntollet. Inspired by the Selma to Montgomery marches in the United States led by Martin Luther King, the march had been called in opposition to an appeal by NI Prime Minister Terence O'Neill for a temporary end to protest in Northern Ireland. The Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association and some Derry nationalists had advised against it (similar to their attempt to stop a civil rights march in October 1968). Supporters of Ian Paisley, led by Major Ronald Bunting, also denounced the march as seditious and mounted counter-demonstrations along the route.

Forty people, many Queen’s University Belfast students and graduates, had left to start a 4 day march from Belfast to Derry on New Year’s Day. That day, a bomb planted by UVF members destroyed a republican memorial at Toomebridge, County Antrim, on the route of the march.

Their numbers grew to a few hundred as they marched, harassed by loyalists and rerouted by the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), before arriving in Derry on the 4th of January.

At Burntollet, 5 miles outside derry, an Ulster loyalist crowd, reported to be in the region of 300, including 100 off-duty members of the Ulster Special Constabulary, attacked the civil rights marchers from adjacent high ground. Stones transported in bulk from William Leslie's quarry at Legahurry were used in the assault, as well as iron bars, bottles and sticks spiked with nails. Nearby members of the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) did little to prevent the violence.

At the time many of the marchers described their assailants' lack of concern about the police presence, and it transpired that dozens of marchers were taken to the hospital. The remainder continued to Derry where they were attacked once more on their way to Craigavon Bridge before they finally reached Guildhall Square, where they held a rally. Rioting broke out after the rally.

Police drove rioters into the Bogside, but did not come after them. In the early hours of the following morning, the 5th of January, members of the RUC charged into St. Columb's Wells and Lecky Road in the Bogside, breaking windows and beating residents. In his report on the disturbances, Lord Cameron remarked that "for such conduct among members of a disciplined and well-led force there can be no acceptable justification or excuse" and added that "its effect in rousing passions and inspiring hostility towards the police was regrettably great."

Terence O'Neill described the march as "a foolhardy and irresponsible undertaking" and said that some of the marchers and their supporters in Derry were "mere hooligans", outraging many, especially as the attackers had evaded prosecution. Loyalists celebrated the attack as a victory over Catholic "rebels".

The ambush at Burntollet irreparably damaged the credibility of the RUC. Professor Paul Bew, an academic at Queen's University Belfast who as a student had participated in the march, described it as "the spark that lit the prairie fire".

That afternoon over 1,500 Bogside residents built barricades, armed themselves with steel bars, wooden clubs and hurleys, and told the police that they would not be allowed into the area. DCAC (Derry Citizens Action Committee) chairman John Hume told a meeting of residents that they were to defend the area and no one was to come in. Groups of men wearing armbands patrolled the streets in shifts.

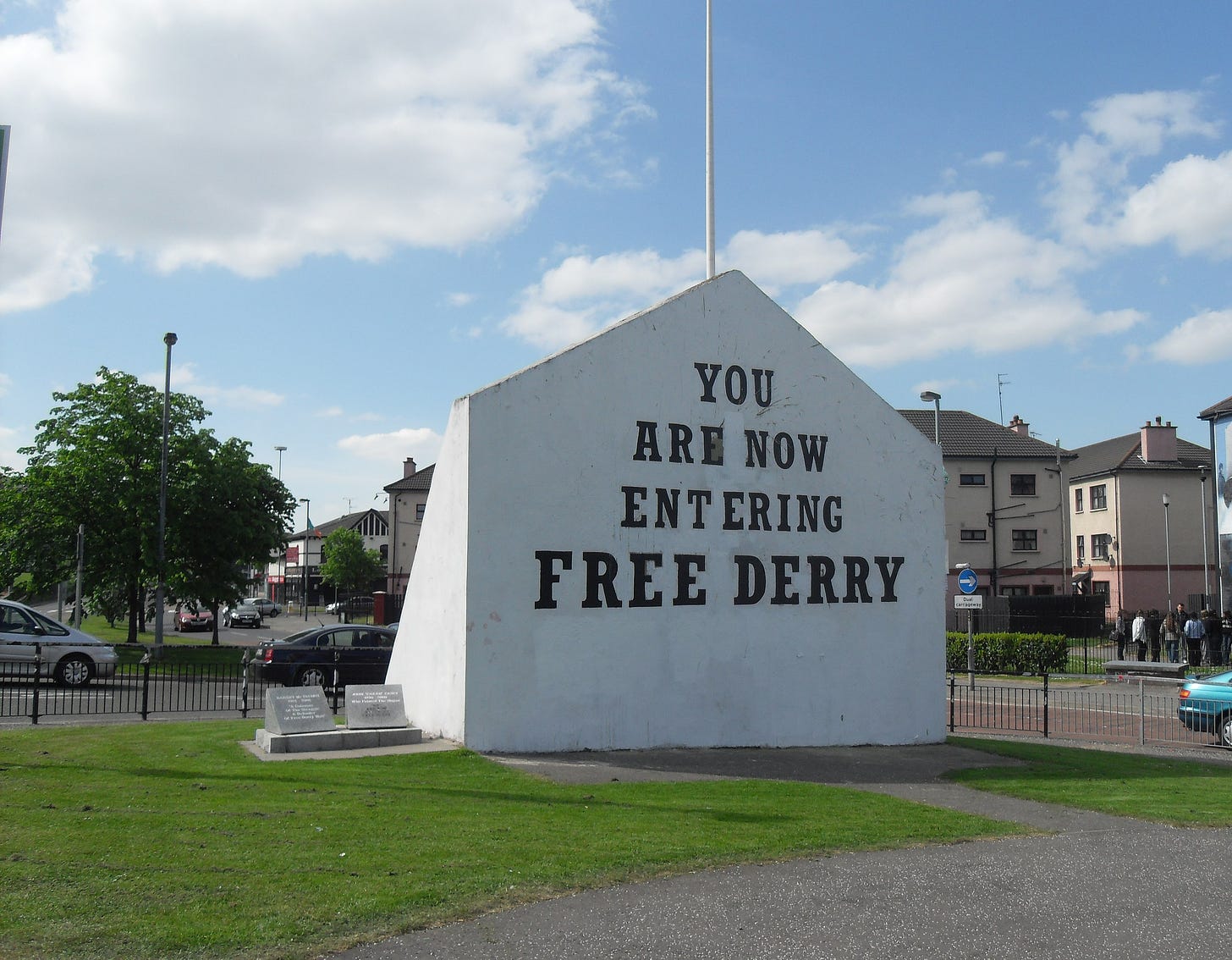

A local activist painted "You are now entering Free Derry" in light-coloured paint on the blackened gable wall of a house on the corner of Lecky Road and Fahan Street. For many years, it was believed that it was John 'Caker' Casey that painted it, but after Casey's death, it emerged that it might have been another young activist, Liam Hillen. The corner where the slogan was painted, which was a popular venue for meetings, later became known as "Free Derry Corner".

On 7 January, the barricaded area was extended to include the Creggan, another nationalist area on a hill overlooking the Bogside. A covert radio station calling itself "Radio Free Derry" began broadcasting to residents, playing rebel songs and encouraging resistance. Many unionists believe that this was a form of propaganda.

On a small number of occasions, different law-breakers attempted to commit crimes but were dealt with by the patrols. Despite all this, the Irish Times reported that "the infrastructure of revolutionary control in the area has not been developed beyond the maintenance of patrols.

Following some acts of destruction and violence late in the week, members of the DCAC including Ivan Cooper addressed residents on Friday, the 10th of January and called on them to dismantle the barricades. The barricades were taken down the following morning.