December 1978: The Green Ring

December 1978 saw US President Jimmy Carter more than double the national park system size. In Northern Ireland, segregation and development were top of the agenda too.

Political Developments in December 1978

The main political development in December was a ‘Note for the Record’ on segregation by A.E. Huckle on the 5th. The note went as follows;

I spent 2 hours on 28 November with Sam McIlwaine, the assistant district development officer in Londonderry (David White being on sick leave) to explain the type of in-house study that was envisaged following the Secretary of State's meeting with William Ross MP and Bishop Eames.

He welcomed the idea of a quick study enthusiastically, in particular the possibility of accurately quantifying the population drift and the effect that this was creating in Londonderry. Much of the planning that had taken place in Londonderry over the last 5 years had, he said, been conducted on the assumption that there was a drift but without any real appreciation of the facts or of the response that should be made to them. There would, he felt, be little difficulty in obtaining the necessary information both as regards population movement and existing government measures in Londonderry, but he felt that there was very little that could actually be done. It was not a case of trying to prevent a drift; the drift had already occurred and might actually be stabilising if not, with improved security, even going slowly into reverse. It was much more a question of seeing what could be done to maintain, and reassure the residents of, the existing small Protestant estates on the west bank of the Foyle. Indeed, he emphasised that we were speaking of about a mere 1,300 Protestant families on the west bank, 400 in the Fountain estate, 400 in Rosemount and 500 in the Glen. Although we did not enter into much discussion about the measures that might be taken (since that was not the purpose of this first contact), he did agree that we were probably embarking on a cosmetic exercise, although there were several positive measures that he felt might, given the necessary political will, be adopted to improve and/or alleviate social conditions in Protestant (and Catholic) estates in Londonderry.

Turning to the particular, he described the changes that had occurred:

NIHE and education statistics were likely to confirm his impression that it was not just a question of population drift but of relative demographic decline; proportionately, the Protestant population of Londonderry had certainly stopped growing if it had not actually reduced. Nor was it just a question of Protestants moving from the west bank to the Waterside; instead many had moved as far away as Antrim and to Craigavon, as well as to Coleraine and the Limavady area. Young people tended to prefer Queen's University or mainland universities to NUU, which was largely Catholic; who then, having got their degrees failed to return. In general terms, the average age level of the Protestant population in Londonderry was probably higher than that of the Catholic community.

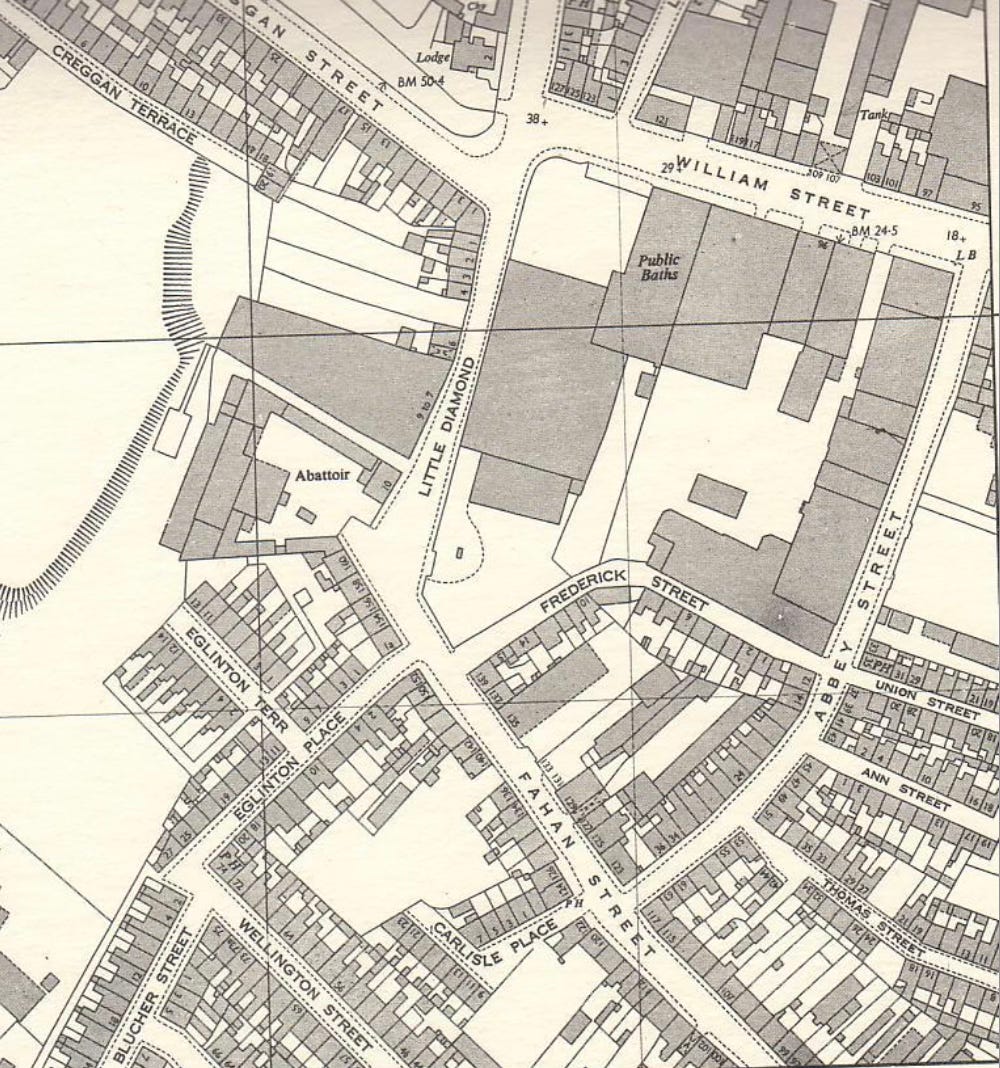

That the drift had been dramatic, a comparison of 'colour' maps over the decade would show. In the 1960s, the area bounded by Abercorn Road and Bishops Street had been 90% Protestant; now it was predominately Catholic. The same applied to the areas around Rosemount Avenue, Oakfield (Marlborough Avenue, Marlborough Road, Marlborough Street), and Belmont. Both the Northland and the Glen (Cloughglass) estates had been thriving Protestant areas; now they were almost mixed estates. The Fountain estate was under less pressure and had been wholly redeveloped with modern housing at reduced density, but the population was old and in decline.

Schools had been particularly affected. The Model Primary School on Northland Road which had once had a population of 7-800 children now only had 250-280.

The Christ Church CofI Primary School which had once had 400 children was now closed and had been turned into a library. The Carlisle Road Presbyterian Primary School and the Hawkin Street Cathedral School were now reduced to about 60-70 pupils each and the Bishops Street Cathedral School had closed. There was no case therefore for a new primary school close to the city centre unless the two remaining primary schools were amalgamated (which would be difficult given the different denominations). Templemore Secondary School, which served the west bank used to have 600 pupils and had now declined to about 300; Clondermot Secondary School on the east bank on the other hand had grown by about the same amount. The Foyle and Londonderry College, the relatively new grammar school serving the whole of Protestant Londonderry, would soon be wholly surrounded by Catholic estates, emphasising its isolation. Already about 40-50 families living in the Waterside preferred to incur the expense of sending their children to grammar schools in Limavady. The theory that the Protestant population may actually be, or have been, in decline might be confirmed by a survey currently in hand on the need for a third primary school in the Waterside. It had always been assumed that this would be necessary but there was some evidence to show that the Education and Library Board had overestimated the requirements.On the whole, housing conditions in Londonderry were good, due to post-war development. The large Catholic estates on the west bank - Creggan, Bogside, Shantallow - were modern and the NIHE proposed soon to develop the Ballymagrorty area, thereby closing the "green" ring around the west side of the city. Most of the west bank is now public sector housing, with private development being confined to the east bank. The large middle-class private estate in Woodburn had been fuelled by the Protestant" moves. It was important also to recognise that the east bank was not wholly Protestant - overall it was about 30-35% Catholic with large Catholic estates like Gobnascale interfacing with Protestant Irish Street. The NIHE were also to decide soon whether to begin a major new Catholic housing development in East Londonderry.

Youth and leisure facilities were poor in Protestant areas on the west bank. The Glen estate had a community hall and a small grassed playing area; Northlands had nothing (though it was close to Brook Park leisure centre) and there was one small community centre in the Fountains estate.

Churches, too, indicated the drift. The century-old Presbyterian Church on St James Street had been closed whereas churches in the Waterside were overflowing.

There had, to some extent, been a relocation of commercial activity to the east bank. Many offices, e.g. solicitors and architects, had been opened on the Waterside and the planning services had come under criticism from the council for allowing change of use applications to go through so easily. A major shirt manufacturer, Welsh Margetson, were to move out of the city centre soon. GTCs were divided on sectarian lines. Springtown GTC was wholly Catholic; Maydown GTC (on the east bank) was Protestant (though with a large minority of Catholic trainees).

In general, therefore, Mr. McIlwaine saw little that could really be done to prevent or reverse a pre-existing trend that had probably already run its course. The supposed threat was largely psychological and territorial and probably could only be removed, if at all, by psychological measures. Londonderry, he said, had never really suffered from the same interface/ intimidation problems so common in Belfast and the security situation had much improved. He did, however, see much in Mr Ross' argument that policing should be improved in County Londonderry. The Strand Road police station was being renovated and a new station was to be built in Racecourse Road Shantallow, but the closure of the local stations e.g. in Lecly Road and Bishops Street had been a retrograde step. A police presence and/or effective policing in the Protestant (or even Catholic) estates on the West Bank would, he said, go a long way to reduce Protestant fears.

If a sub-group in Londonderry were to be set up to provide the basic factual material for a DOE-led steering group in Stormont, he would envisage representation from the Education and Library Board (Mr John Slieveman), NIHE (Miss Kirk, Mr Heading) and the RUC, being full members under David White's chairmanship with DMS, DOC and possibly Army involvement as necessary.

Shootings in December 1978

14/12/78 - A Prison Officer, John McTier (33), died three days after being shot by the IRA while leaving Crumlin Road Prison, Belfast.

19/12/78 - A British soldier, James Burney (26), was shot dead by an IRA sniper while guarding other soldiers who were raiding a house on Baltic Avenue, New Lodge, Belfast.

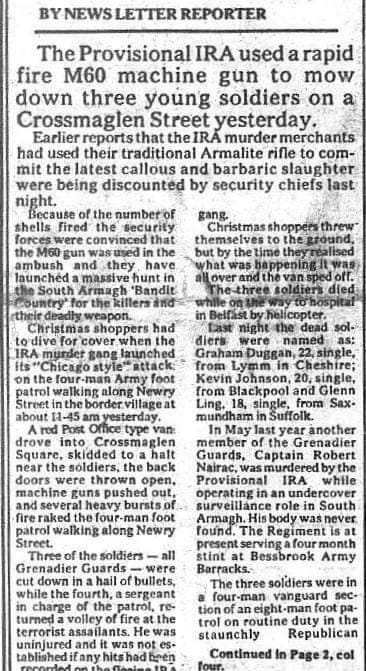

21/12/78 - A four-man IRA unit ambushed a British patrol near St. Patrick's church in Crossmaglen, County Armagh. The IRA unit fired a large number of shots from three Armalites and one AK-47. Three British soldiers, Graham Duggan (22), Kevin Johnson (20), and Glen Ling (18), were killed. The army unit returned fire, but the IRA unit made its escape in an armour-plated van.

If you’d like to support the newsletter, why not buy me a ☕️ ?

Bombings in December 1978

01/12/78 - The IRA carried out 11 bomb attacks on towns across Northern Ireland. There were no injuries.

11/12/78 - The INLA claimed responsibility for several bombs planted outside premises in Belfast city centre: a bank on the Antrim Road, an insurance company office on Clarence Street, an electrical goods showroom on the Antrim Road and Water Department headquarters on Verner Street. A fifth device was defused outside a bank in Bedford Street.

12/12/78 - Four people were injured by parcel bombs in Belfast and Lisburn. Three of those injured were the wives of prison officers, and the fourth was a postman.

15/12/78 - The INLA planted bombs outside two bank premises at Sackville Street and Shipquay Street, Derry. One device was defused, the other caused only minor damage. Bomb attacks on two banks in the Shantallow area of the city were aborted because the unit involved was delayed.

15/12/78 - The INLA injured a British soldier in a hand grenade attack at Castle Gate, Waterloo Street, Derry.

17/12/78 - Provisional IRA bombs exploded in Manchester, Liverpool, Coventry, Bristol and Southampton. A bomb that exploded at Maggs Department Store in Clifton, Bristol, injured 18 people.

17/12/78 - A Maze prison officer was injured when a mercury-tilt switch bomb exploded under his car near Lisburn. (This was the first time the INLA used this type of device).

Thanks very much for reading. I hope you found it interesting and will come back on Sunday!

I appreciate everyone who recently hit that heart icon ❤️ at the bottom. It makes it easier for other people to find this newsletter.

Thanks for the support!

I’ve also recently released Tales of The Troubles: Volume 1. The Early Years - 1960s. Check it out. It would be a great addition to your library or a gift for someone for Christmas. Stay tuned for Volume 2, covering the 1970s.

If you’d like to let me know what you think of today’s instalment, please comment below.

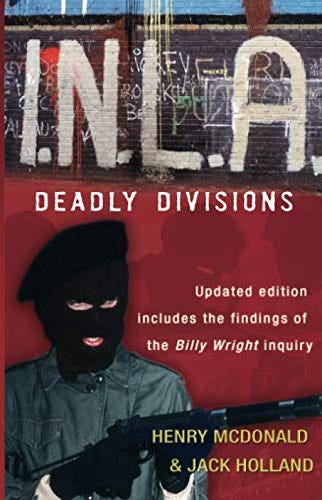

Some recommended reading based on research for this instalment.

Shadows: Inside Northern Ireland's Special Branch by Alan Barker.